A new study, published last week in Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, suggests a minimally simple way for people with cirrhosis to avoid these long-term effects.

Ammonia is a natural by-product of protein digestion in the human body, but it is highly toxic if it reaches the brain.

Ammonia is released from food by bacteria as proteins are broken down in the intestine. It also passes to the liver, which converts it into a less toxic form, urea, which is eliminated in the urine.

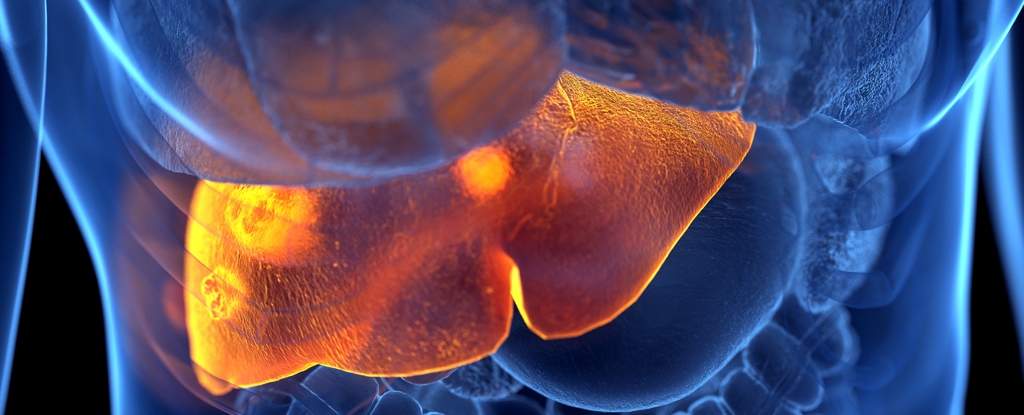

Protein-rich foods, especially those of animal origin, are generally considered part of a healthy diet, but this new study suggests that moderating meat intake could ease the burden on people with cirrhosis, the most advanced stage of liver disease.

The more meat you eat, the more ammonia your liver has to process, and a damaged liver will find it harder to do this. This problem leads to a concentration of ammonia in the blood, which is associated with hepatic encephalopathy (HE), a type of cognitive decline.

Hepatic encephalopathy can be gradual or sudden with liver failure and in some cases can be associated with coma where swelling of the brain tissue can lead to death.

Thirty male patients with cirrhosis treated at the Richmond Veterans Affairs Medical Center took part in the study, although not all of the participants were veterans.

All were habitual meat eaters, with similar Western-style diets, and had similar gut bacteria profiles before the experiment. Half of them had previous HE.

The patients were divided into three groups, each given a different type of burger at mealtimes. All the burgers contained exactly 20 grams of protein: pork/beef burgers for the first group, a vegetarian meat substitute for the second group and a vegetarian bean burger for the third.

The burgers were served with wholemeal buns, low-fat French fries and water. No extras were allowed.

The only essential difference between the groups was the protein source of the burgers, but this difference had a considerable effect on the blood tests taken before meals.

Serum ammonia levels in the blood were elevated in the beef burger patients, compared to the other two groups and to the baseline levels of all the patients before the meal.

Patients with previous HE showed higher levels of serum ammonia in the blood in general, but the participants in the meat group also recorded a spike in these levels one hour after eating the burger - a trend unique to their group.

"It was exciting to see that even small dietary changes, such as having a meatless meal once in a while, could benefit the liver by reducing harmful ammonia levels in patients with cirrhosis," says Jashmohan Bajaj, a gastroenterologist at Virginia Commonwealth University and lead author of the study, quoted by Science Alert.

"Liver patients with cirrhosis should know that making positive changes to their diet need not be a difficult or overwhelming task," adds Bajaj.

Although the study is preliminary and the measurements were taken after just one meal, the team is confident enough in the results to suggest that doctors start implementing them, encouraging patients with liver disease who eat meat to incorporate vegetarian alternatives into at least one meal a day.

Other research shows that eating less meat and more vegetables is associated with longer, healthier lives, a lower risk of cancer and a way of contributing to a more sustainable world.