In a new study, published this Tuesday in Nature Neuroscience, researchers from Imperial College London measured the elimination of toxins and the movement of fluids in the brains of rats and found that this elimination was greatly reduced during sleep and under anesthesia.

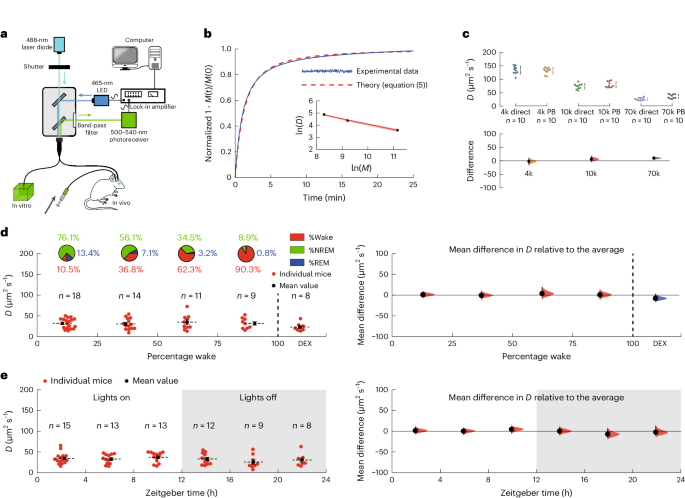

The researchers used a fluorescent dye, observing how quickly the dye moved from one area of the brain to another and was eliminated from the animals' brains. This allowed them to directly measure the rate of elimination of the dye from the brain.

The authors of the study found that the elimination of the dye was reduced by around 30% in the sleeping rats and by 50% in the anaesthetized rats, compared to the rats kept awake.

The main theory was that sleep improves the elimination of toxins from the brain, which happens through the glymphatic system - a mechanism that eliminates waste from the central nervous system.

This theory has never been conclusively confirmed and previous studies were based on indirect means of measuring the flow of fluids through the brain.

"The field has been so focused on the idea of purification as one of the main reasons why we sleep, that we were very surprised to observe the opposite in our results," says Nicholas Franks, lead author of the study, in a statement from Imperial College London.

The size of the molecules can affect how quickly they move through the brain and some compounds are eliminated through different systems. However, it has not yet been confirmed to what extent the results are generalizable.

"Sleep disturbance is a common symptom in people living with dementia, but we don't yet know whether it is a consequence or a determining factor in the progression of the disease. It is possible that good sleep helps to reduce the risk of dementia for reasons other than the elimination of toxins," concludes study co-author William Wisden.

The researchers also want to find out how sleep reduces the elimination of toxins from the brain in rats and explore whether their findings are applicable to humans.