Researchers have discovered evidence that the ancient Egyptians tried to surgically treat cancer more than 4000 years ago. This discovery, published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine on May 29, could change our understanding of the origins of modern medicine.

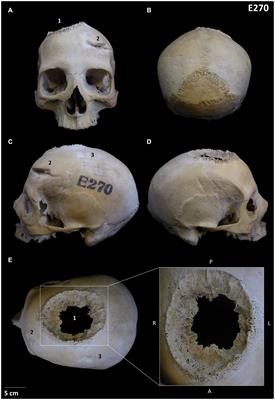

The study involved the analysis of a human skull from the Duckworth Collection at the University of Cambridge, dating from between 2686 and 2345 B.C. This skull showed a large primary tumor and more than 30 smaller metastatic lesions.

Around these lesions there were cut marks, possibly made with a sharp metal instrument, indicating an attempt at surgical intervention. The patient is thought to have been a man in his 30s.

Previously, the oldest known description of cancer was found in the Papyrus of Edwin Smith, from around 1600 B.C. This document, which is thought to be a copy of even older works, described various breast tumors, but stated that there was “no treatment” available for them.

“This is the first evidence of a surgical intervention directly related to cancer,” said Edgard Camarós Perez, a paleopathologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain and co-author of the study. “This is where modern medicine begins”.

In addition to this skull, the researchers examined another skull of a woman who lived between 664 and 343 B.C. She was around 50 years old at the time of her death and also showed signs of cancer, with a large lesion on her skull.

However, unlike the man, she had two additional traumatic injuries that had healed, suggesting that she had survived significant wounds inflicted by a sharp weapon.

This implies that ancient Egyptian medicine was advanced enough to treat serious trauma, but not cancer, reports Live Science.

These findings indicate that cancer was a difficult frontier for ancient Egyptian medicine. Despite their efforts, the successful treatment of cancer remained difficult. “Without the full clinical history of the patients, we cannot fully understand the extent of the cancer they suffered,” noted Camarós Perez.

The research team wants to go even further back in time to find out more about humanity's long fight against cancer.

“Knowing that the ancient Egyptians were trying to understand cancer surgically over 4,000 years ago, we are convinced that this is just the beginning of a much older story,” says Camarós Perez.