A team of researchers from Imperial College London has created a wallet and part of a shoe using genetic engineering of the kombucha bacteria to produce melanin.

For sustainability-conscious fashionistas, materials made from fast-growing, environmentally-friendly bacteria already offer an appealing alternative to leather or artificial plastic substitutes.

However, coloring or adding patterns to these bacterial textiles still involves using environmentally harmful dyes.

A study published last week in the journal Nature Biotechnology now offers a solution: using genetic engineering of bacteria to produce melanin pigment - so that the material can dye itself.

"This is an example of how biology can provide products that not only have remarkable properties, but can also be manufactured with a very low environmental footprint and be sustainable," says Sara Molinari, a biologist at the University of Maryland who was not involved in the study.

Bacteria-generated textiles are "a completely new approach to manufacturing materials", she adds.

The leather substitute is made from cellulose, an essential structural material in plants that is also produced by several species of bacteria.

In recent years, researchers and designers have started producing textiles from bacterial cellulose as an alternative to leather and synthetic fur, some of which are already on the market.

The durable textile, which scientists can rapidly grow into customized shapes, has many of the same properties as traditional leather.

But while bacterial cellulose textiles have less of an environmental impact than leather or plastic, they are by nature brown or beige in color - and are usually colored using traditional dyeing processes, which use large amounts of water and release harsh chemicals into the environment.

In the new study, researchers from Imperial College London tried to find out whether it would be possible to persuade bacteria to produce dark-colored cellulose.

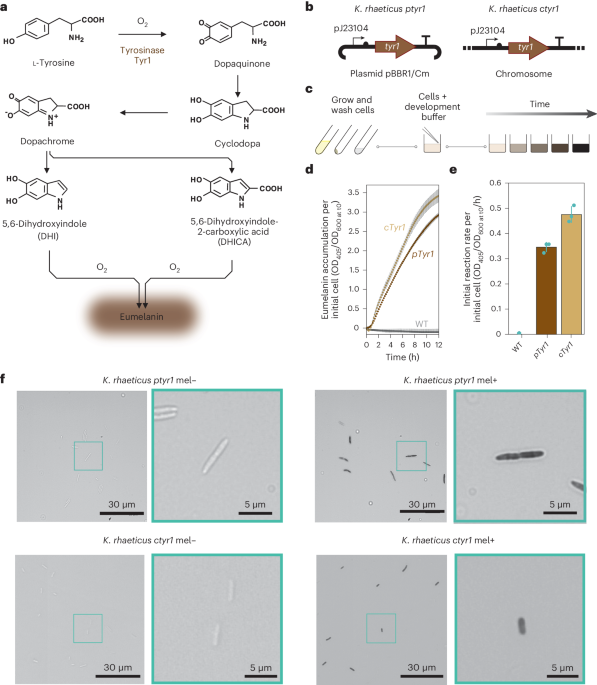

To find out, they genetically engineered a cellulose-producing bacterium, Komagataeibacter rhaeticus - the same bacterium that helps ferment kombucha - by adding a gene from another bacterium that produces the pigment black melanin.

Melanin is the generic name for a class of polymeric compounds derived from tyrosine, which gives color to tissues throughout nature, including hair, human skin and eyes.

The first experiments were not promising. The cellulose material appeared pale and faded, rather than dark black as the researchers had hoped.

The authors of the study then discovered that the medium used to grow K. rhaeticus in the laboratory became more acidic as the bacteria grew, hindering the production of melanin.

To solve this problem, the researchers developed a two-step process: after producing the cellulose, they submerged the material in a vibrating bath with the same pH as the water, and a rich black color quickly developed.

Once the desired color was achieved, the scientists grew sheets of bacterial cellulose to the size and shape needed to make a wallet and the top of a shoe, and used a heat press to eliminate the remaining bacteria.

"The color was really impressive," biologist Tom Ellis, a researcher at Imperial College and corresponding author of the study, told Science magazine. "Much more than we imagined."

Using the same genetic engineering technique as the kombucha bacteria, the team of researchers also created designs on the textiles, which produced melanin pigment only when exposed to blue light, which was projected in patterns onto the cellulose sheet.

The melanin-dyed textiles appear to be just as durable as their undyed cellulose counterparts, the researchers point out

"There is a great demand for this type of solution in fashion companies - microbial textiles made using biotechnology techniques," says Ellis.

Apparently, bacteria are the new black.