Engineers at Johns Hopkins University already knew that swimming in groups gives fish additional protection against predators, but they wanted to investigate whether this behavior also helps to reduce their noise.

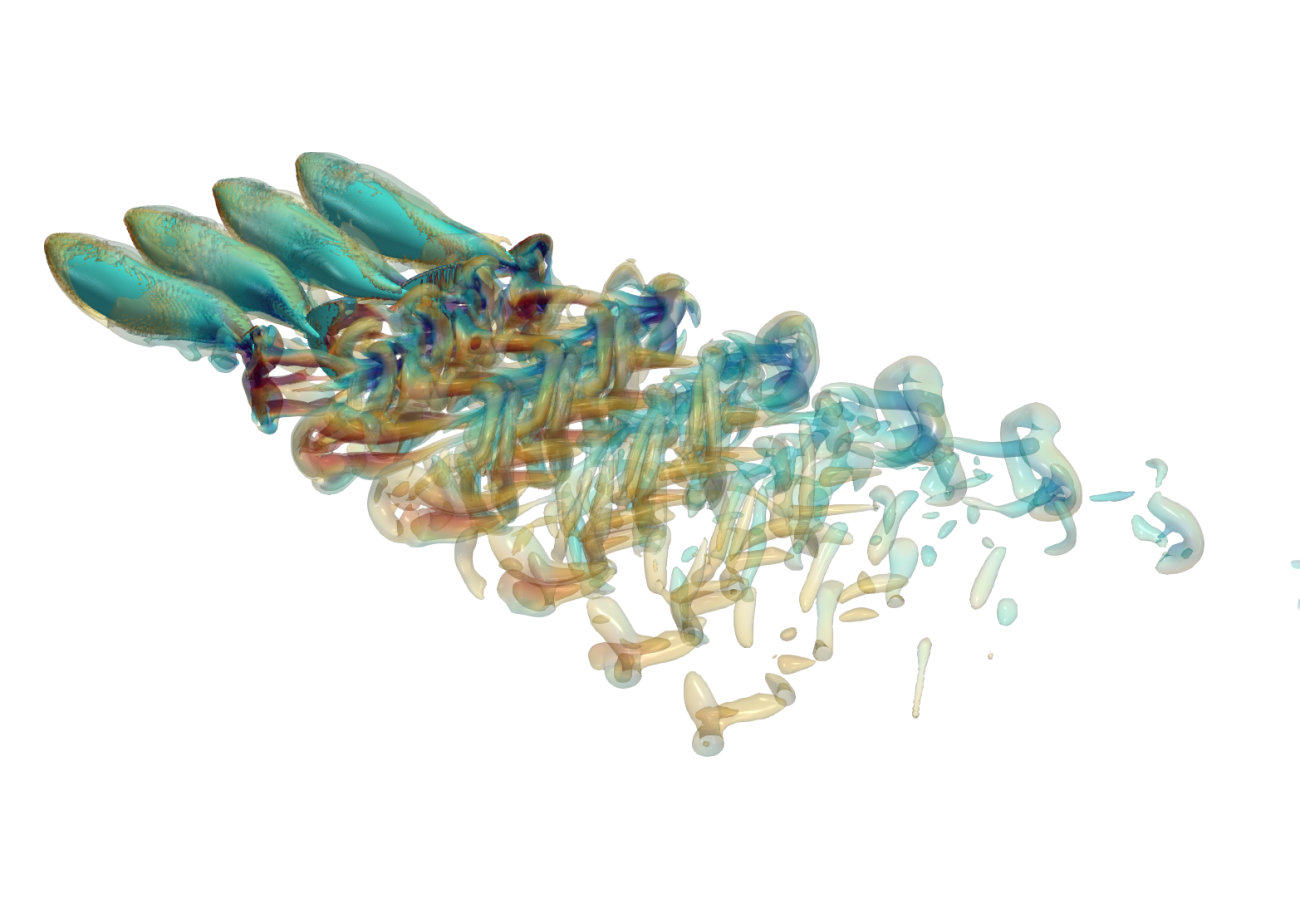

To do this, the team created a 3D model, based on mackerel, to simulate different numbers of fish swimming in schools, changing their shapes, the proximity with which they swam and the synchronization of their movements.

The model created, which applies to several species of fish, simulates from one to nine mackerel swimming in a school.

The conclusions left no room for doubt: a school of fish moving synchronously together was surprisingly effective at reducing noise. The experiment found that a school of seven fish made as much noise as a single fish.

"Our results suggest that the substantial decrease in their acoustic signature when they swim in groups, compared to swimming individually, may be another factor that drives shoaling," explained researcher Rajat Mittal, in a statement from Johns Hopkins.

The reason behind the reduction in sound is the synchronization of the movement of the tail - or, in fact, the lack of it.

According to the model, if the fish moved in unison, flapping their tail fins at the same time, the sound increased and there was no reduction in total sound. However, if they alternated tail beats, the fish canceled out each other's sound.

In addition, the research concluded that tail fin movements that reduce sound also produce flow interaction between the fish, allowing them to swim faster using less energy.

The scientific article with the recent findings was published in Bioinspiration & Biomimetics.