The new study, carried out by scientists from the Zuckerman Institute at Columbia University, analyzed two species of mice: the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), and the Oldfield mouse (Peromyscus polionotus).

According to Phys, previous research has shown that these two species behave in very different ways. While the former gets involved with several partners, the Oldfield's rat mates with just one throughout its life.

However, these same investigations have also shown that these species are evolutionary sisters, based on analysis of the skull, teeth and other anatomical features, as well as their genetics.

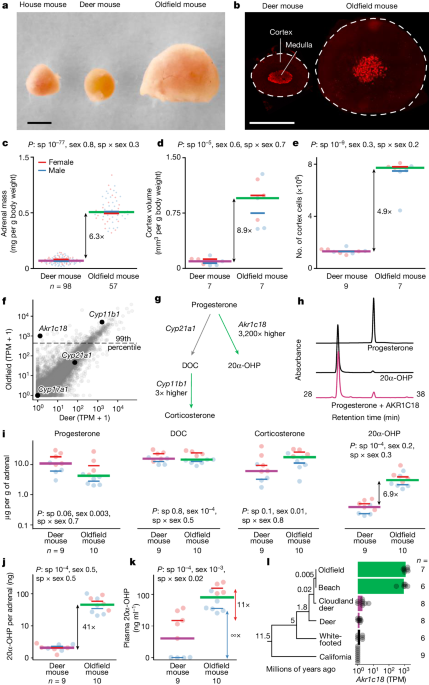

In this study, to find out why these close relatives behave so differently, the scientists studied their adrenal glands, a pair of organs, located in the abdomen, which produce many hormones important for behavior, such as stress hormones, namely adrenaline, but also a series of sex hormones.

The adrenal glands of these rats turned out to be surprisingly different in size. In adults, the adrenal glands of monogamous mice are about six times heavier than those of their relatives.

Further genetic analysis revealed that one gene, Akr1c18, was much more active in the monogamous animals. The enzyme that this gene codes for helps create a little-studied hormone known as 20⍺-OHP, which is also present in humans and other mammals.

In the laboratory, the increase in the hormone 20⍺-OHP boosted feeding behavior in both species. But the most curious thing is that these glands are normally divided into three zones, unlike the adrenal glands of monogamous rats, which have a fourth zone.

In the cells of the so-called zona inaudita, the researchers found that 194 genes, including Akr1c18, were much more active compared to the same genes in other adrenal cells. The analyses also made it possible to identify key genes underlying the development and function of the zona inaudita in the Oldfield mice.

This completely new structure seems to have evolved rapidly. Genetic mutations accumulate in genomes at roughly predictable rates over time, so by measuring the number of mutations that distinguish these species, scientists have estimated that this new type of cell has evolved over the last 20,000 years.

The evolution of monogamous behavior still remains very uncertain, although researchers suggest that monogamy may increase the chances of parents cooperating to care for their offspring, as they feel more confident that the offspring are theirs.

This work, whose scientific article was published in Nature, argues that the recently discovered adrenal cells promote the parenting behavior typical of monogamy and may increase the chances of survival of the offspring.